tl;dr summary

- If enhanced ACA subsidies expire, premiums for 24 million marketplace enrollees will roughly double (and sometimes triple). Millions will lose coverage outright.

- Marketplace PPOs are already scarce: only 14% of plans are PPOs, and 37% of Americans live in states with zero PPO options. Subsidy expiration accelerates this decline.

- Out-of-network reimbursement is a pillar of the SUD industry. 35.9% of residential SUD admissions are out-of-network (vs 1.7% for all other medical care), and many mid-market facilities depend heavily on OON PPO billing for revenue stability.

- When subsidies disappear, the pool of people with insurance that covers out-of-network treatment shrinks sharply. That contraction flows directly into weaker lead volume, higher CAC, lower conversions, and tighter cash flow.

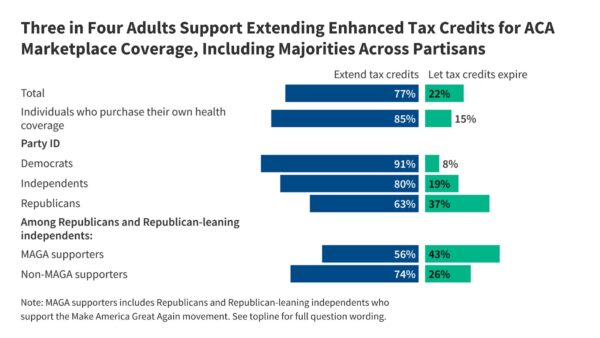

- Public support for extending subsidies is overwhelming (77%), but Congressional action is uncertain. Planning on political rescue is not a strategy.

- At the end of the article, I outline the critical questions every treatment operator must be able to answer now to avoid being blindsided.

I was watching the government shutdown negotiations collapse in real time last Sunday night, and I couldn’t sleep. Not because I’m particularly invested in Congressional theater (although, admittedly, I am a bit of a policy wonk), but because I know exactly what it means for the addiction treatment industry when 24 million people are about to see their health insurance premiums double overnight.

I kept thinking about this woman I’ll never meet. She’s 28, a few months sober, working a retail job that doesn’t offer benefits. She bought a marketplace PPO last year because she knew she’d need ongoing outpatient support and wanted the flexibility to see her therapist out of network. You know, the kind of flexibility that really matters when you’re trying to stay alive. With the ACA subsidies, her premium is about $150 a month. Manageable. Without them, it jumps to $380.

She can’t afford that. So she drops coverage.

Three months later, she relapses. She starts calling treatment centers, but without insurance, her options narrow fast. The good programs have three-month waitlists. The ones with openings don’t take uninsured clients, or they quote her $30,000 – which she can’t afford, either. She keeps using. Maybe she gets another chance, sure. But maybe she doesn’t.

This isn’t just a hypothetical scenario I’m constructing to make a point. This is the predictable, mechanical outcome of what just happened in Congress.

And if you run a treatment facility, you need to understand how this is about to reshape your business.

Here’s What Actually Happened With the Subsidies

Let me start with the policy basics, because if you haven’t been tracking this closely, the details matter.

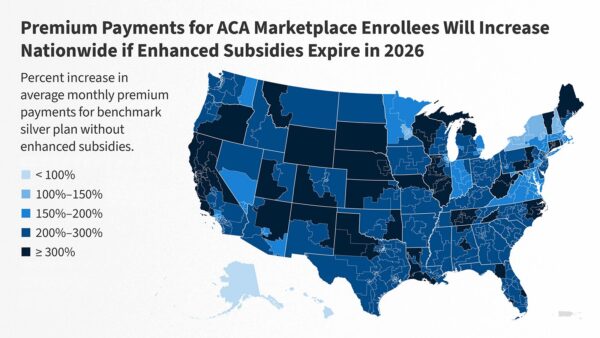

About 24 million people buy coverage on the ACA marketplaces. These are individuals and families who, instead of receiving health insurance as a benefit from their employer, are shopping for plans on their own. The enhanced premium subsidies that came from the American Rescue Plan in 2021 and got extended through the Inflation Reduction Act made those premiums dramatically more affordable. We’re talking premium cuts to the tune of 50%, 60%, sometimes 70% for people who qualify (which is a lot of people).

Without those subsidies, premiums for marketplace enrollees will roughly double on average. For some people, especially older enrollees or people in high-cost states, they’ll nearly triple. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that 2 to 4 million people will lose coverage entirely if the subsidies expire. Other independent models suggest that 7 million or more people will drop their marketplace plans because they can’t afford the new premiums.

And the addiction treatment industry is uniquely exposed to what happens next.

Out-of-Network Care Is a Critical Part of How This Industry Works

Here’s something that most people outside this industry don’t understand, and that most people inside the industry don’t talk about openly: Out-of-network care is dramatically more common in substance use treatment than in virtually any other area of healthcare.

A recent study published in 2025 found that 35.9% of residential and sub-acute SUD encounters occur out of network. For context (and this is truly eye-popping) only 1.7% of other types of medical care happen out of network. We’re talking about a 20-to-1 difference in out-of-network utilization rates.

But why is that? Many mid-market facilities, particularly those offering specialized care or multi-level treatment programs, rely heavily on out-of-network reimbursement. In our work at Faebl, we routinely see facilities where 50-70% or more of total revenue comes from out-of-network PPO billing. Some facilities operate with zero in-network contracts at all. Others maintain a handful of in-network relationships with major payers, but still depend on out-of-network PPO clients for a meaningful portion of their revenue.

Even facilities that have robust in-network contracts actively seek out PPO clients. They’ll tell you privately that they like those policies because the reimbursement rates are often substantially higher than their negotiated in-network day rates. For example, where an in-network contract might pay them $800 a day, an out-of-network PPO claim might reimburse double or even triple that amount. That difference is not trivial when you’re trying to run a 40-bed facility and maintain a low client-to-staff ratio with expert clinical staff who deserve to be paid well.

This is standard operating procedure for non-corporate, non-Medicaid facilities in the mid-market. Now here’s the problem, and it’s a big one: PPO policies are already vanishing from ACA marketplaces. And if the subsidies expire, that process accelerates dramatically.

The PPO Problem Is Already Critical

In an ideal world, the pathway to treatment for many people looks something like this: Buy a PPO on the marketplace. Use the out-of-network benefit to access a facility that has openings and offers the care you need. Pay your deductible and coinsurance. Get treatment. Stay alive.

Except, here’s the problem: Only 14% of marketplace plans nationwide are PPOs, according to recent data from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. That number alone should alarm you. But it gets worse when you zoom into specific markets.

37% of Americans live in states where there are zero PPO options on the exchange. Zero. If you live in New York or Texas, two of the largest states in the country, you cannot buy a PPO on the ACA marketplace. You can buy an HMO. You can buy an EPO. But you cannot buy a plan that offers meaningful out-of-network benefits.

What’s more, behavioral health networks on ACA marketplaces are especially narrow. Research from Penn LDI shows that marketplace networks for mental health and substance use treatment are significantly more restricted than networks for primary care or other specialties. This matters because even when people have insurance, they often can’t find an in-network provider who has availability or who offers the level of care they need, forcing them to rely on out-of-network benefits that may not be available to them.

When subsidies expire, the pathway to treatment runs into some serious roadblocks.

The Chain Reaction When Subsidies Disappear

Premiums double, or worse. People who were paying $150 a month are now paying $350 or $400. Some of them grit their teeth and pay it. Many of them can’t. They drop coverage.

The people who drop coverage aren’t random. They’re disproportionately younger and healthier. So the risk pool that remains gets older and sicker. Insurance companies look at that risk pool and see that their costs per enrollee are going up. They respond by raising premiums further, by replacing PPOs with more cost-manageable plans like HMOs or EPOs, or by pulling back from certain markets entirely.

PPO availability, which is already scarce on the marketplaces, shrinks even more. In some states, PPOs disappear completely. The individual market becomes dominated by narrow-network HMOs and EPOs that offer little to no out-of-network coverage for substance use treatment.

The addressable market for facilities that depend on out-of-network reimbursement contracts. Hard.

Let me spell out what that means in practical terms: Fewer people have insurance that covers out-of-network treatment. Your cost per acquisition for PPO clients goes up because there are fewer of them and they’re harder to find. Your conversion rates drop because people can’t afford the out-of-pocket costs even when they have insurance. So unless you have a coherent strategy to diversify your payer mix, your revenue becomes less predictable and your cash flow tightens.

For some facilities, this represents a genuine threat to their ability to continue operating. I’m not being dramatic here. I’m describing what I see as the potential outcomes of this policy change – based in part on similar outcomes in similar past periods, when subsidies were less generous. We’ve seen this movie before.

The Ripple Effects Go Well Beyond the Marketplace

If you’re thinking that this is just a marketplace problem and your facility primarily serves people with employer-sponsored insurance, you’re not necessarily insulated from this.

Mercer, one of the largest benefits consulting firms in the country, projects a 6.5% increase in per-employee health benefit costs in 2026. That’s the largest single-year jump in more than 15 years. 59% of employers say they expect to make cost-cutting changes to their health plans in response to rising costs.

Why are employer costs going up? Part of it is general healthcare inflation. But part of it is the shifting dynamics in the insurance market. When millions of people drop marketplace coverage, some of them shift into employer plans. When the marketplace risk pool gets sicker, it puts upward pressure on premiums across the entire insurance market. Insurance companies don’t operate the marketplace and employer plans in completely separate universes. The costs in one market affect pricing in the other.

What this means for treatment centers is straightforward: Even your clients with employer-sponsored PPO coverage may face higher out-of-pocket costs, which affects your conversion rates. They may face longer financial clearance processes as they try to figure out whether they can afford treatment. They may delay seeking care until their condition worsens, which means higher acuity at admission and more complex treatment needs.

There’s also a longer-term structural shift happening that’s easy to miss if you’re focused on the immediate crisis. If marketplace PPOs continue to disappear, PPO coverage becomes increasingly concentrated in large employer plans. The individual market, where many people seeking addiction treatment buy their coverage, becomes dominated by narrow-network HMOs and EPOs.

That’s a permanent change to the treatment landscape, even if subsidies eventually get restored. The pathways to out-of-network care shrink and don’t fully come back. Consumer behavior shifts. Facilities adapt their models. And the industry that exists in 2027 or 2028 looks different from the industry that existed in 2024.

Three Ways This Could Actually Play Out

I don’t pretend to have a crystal ball about how this ends. But I do follow, think about, and talk about this stuff for a living, and as I see it there are three plausible scenarios; you should be thinking about which one you’re preparing for.

Scenario One:

Subsidies expire and stay expired. This is what I’m treating as the baseline assumption until I see evidence otherwise. Premiums double. Between 2 and 7 million people lose coverage, depending on which model you trust. PPO availability on marketplaces shrinks further or disappears entirely in more states. The individual market becomes dominated by narrow-network HMOs that don’t support out-of-network treatment access.

Facilities that rely heavily on out-of-network reimbursement start to experience revenue pressure. Some respond by pursuing in-network contracts with major payers, but that often means accepting meaningfully lower day rates. Some consolidate with other facilities to achieve scale. Some close.

If this scenario materializes, you’ll start feeling it within 3 to 6 months, right when the Q1-Q2 2026 admissions cycle peaks. January through March is typically the highest-volume period for treatment admissions. If marketplace enrollees are dropping coverage or switching to narrow-network plans during the 2025 open enrollment period, you’ll see the impact in your lead volume and conversion rates by February.

Scenario Two:

Congress panics and passes a short-term patch. This is possible. The politics of subsidy expiration are unfathomably bad for the party in power, and we may see enough Republicans break ranks to pass a 12-month extension to get past the 2026 midterms.

If that happens, you get a temporary reprieve, but the fundamental uncertainty remains. Marketplace enrollees don’t know if their subsidies will be there next year, so some of them drop coverage anyway or switch to cheaper plans with narrower networks. Enrollment gets confusing. Admissions forecasting becomes a little harder because you can’t predict what your payer mix will look like.

You face volatility rather than catastrophe, which… sure, is technically better. But volatility is still expensive. You can’t plan capital expenditures. You can’t confidently expand or hire. You spend more on marketing because lead quality is inconsistent. The turbulence drags through 2026 and possibly into 2027 depending on when Congress actually makes a long-term decision.

Scenario Three:

Long-term restoration after the midterms or after 2028. Eventually, the subsidies probably come back. 78% of Americans support them, including majorities of both parties. That level of public support is hard to ignore indefinitely.

But here’s the thing: By the time subsidies get restored, the marketplace will have already shifted. Insurers will have pulled back from offering PPOs in more states. Consumers will have switched to different plan types or dropped coverage entirely. Facilities will have adapted their business models, either by going in-network, by shifting to different payer mixes, or by closing.

The industry doesn’t snap back to the 2024 model. It adapts to a new normal. Fewer PPOs. More people in employer-sponsored HMOs instead of individual market PPOs. More facilities with in-network contracts and lower margins. The landscape looks different, and some of the changes are permanent even after subsidies return.

The Questions You Need to Be Able to Answer Right Now

If you run a treatment facility, here are the questions you need to be asking yourself. If you don’t know the answers to these, I would strongly encourage you to pull your team together and find them, or you may not be prepared for what’s coming.

What percentage of our payer mix comes from marketplace PPO policyholders? Not just PPOs in general. Marketplace PPOs specifically. Do you even track that distinction in your data? Most facilities don’t. But if 20% or 30% of your admissions come from people who bought coverage on the ACA marketplace, and those people start dropping coverage or switching to HMO plans, you need to know that – and have a plan to replace that revenue. (Incidentally, Faebl can help you construct that plan. Schedule a consultation to talk through your specific situation.)

Do we know our true cost per acquisition for PPO clients? I’m not talking about your average cost per admission across all sources. I’m talking about what it actually costs you in marketing spend to acquire a PPO client specifically. Because if the number of PPO policyholders in your market drops by 25%, your cost to acquire a PPO client is going to go up. Can you afford that? Do you have a plan to mitigate this?

What would happen to our revenue if admissions from marketplace PPOs fell by 20 to 30%? Don’t just guess. Actually run the model. If you’re doing 200 admissions a year, and 50 of those admissions come from marketplace PPO clients, and that drops to 35, what happens to your revenue? What happens to your margins? Can you absorb that? For how long?

Have we modeled in-network rates with our largest potential payers? If you’re currently operating as an out-of-network provider, have you actually sat down with Aetna or Cigna or United and asked what their in-network rates would be? Do you know what the financial impact would be if you went in-network? Some facilities assume that going in-network means a 30% or 40% reduction in reimbursement. For some payers, it’s worse than that. For others, it’s not as bad as you think. But you need to know the actual numbers for your specific situation.

Do we have clean data on our denials, write-offs, and financial clearance timelines? Out-of-network claims are already harder to collect than in-network claims. If your client base shifts toward people with higher out-of-pocket costs, or toward people who are on the edge of being able to afford treatment, your denial rates and bad debt are going to go up. Do you have systems in place to track that? Can you identify which payers are getting slower or stingier with reimbursement? Can you adjust your financial clearance process in response?

Are we prepared to shift marketing strategy if PPO lead volume softens? If you’ve been running the same Google Ads strategy and the same insurance-focused messaging for the last three years, and suddenly the number of people searching for treatment who actually have PPO coverage drops by 25%, what’s your plan? Do you shift toward cash-pay messaging? Do you emphasize financing options? Do you target different geographic markets where PPO availability is better? Or do you just keep running the same strategy and watch your cost per admission go up? (Again, not to toot our horn, but this is where Faebl comes in.)

Are we tracking state-by-state changes in marketplace PPO availability? If you’re licensed to operate in multiple states or you market nationally, you need to know which states are losing PPO options on the marketplace and which states still have decent availability. Because your marketing spend needs to take this into consideration: Should you be shifting toward markets where people can still buy PPO coverage, and away from markets where the only options are narrow-network HMOs? How does the availability of certain employer-sponsored plans change this calculus?

If you don’t have answers to these questions, you’re flying blind. And you’re running out of time to get the answers before they show up as problems on your P&L.

The Politics Are Absurd, But That Doesn’t Help You

I’m taking a point of privilege here, because this honestly has been making my head explode all week: 77% of Americans support extending the enhanced ACA subsidies. Not 78% of Democrats. 78% of everyone. That includes 91% of Democrats, 80% of independents, 63% of Republicans and 56% of self-identified MAGA supporters. This is one of the most broadly popular policies in recent American history.

Which means there’s a decent chance the subsidies eventually get restored, either because enough Republicans break ranks to pass an extension, or because Democrats win back control of Congress in 2026 and pass it then, or because whoever wins the presidency in 2028 makes it a priority.

But “eventually” doesn’t help you right now. Open enrollment is happening right now. People are making coverage decisions right now. The Q1 2026 admissions cycle is gearing up right now. If you’re waiting for Congress to fix this before you start planning for the possibility that they don’t, you’re already behind.

Some members of Congress just decided to let this happen despite knowing what the consequences would be. Whether they reverse course 6 months or 12 months or 18 months from now doesn’t change the fact that millions of people are going to lose coverage in the meantime. It doesn’t change the fact that facilities are going to face serious revenue pressure. It doesn’t change the fact that access to care is going to be restricted for hundreds of thousands of people who desperately need it.

That’s the reality. You can be mad about it. I’m certainly mad about it. But being mad doesn’t change what you need to do to prepare.

Why I’m Writing This

I’m taking a point of privilege here, because this honestly has been making my head explode all week: 77% of Americans support extending the enhanced ACA subsidies. Not 78% of Democrats. 78% of everyone. That includes 91% of Democrats, 80% of independents, 63% of Republicans and 56% of self-identified MAGA supporters. This is one of the most broadly popular policies in recent American history.

First, while I am admittedly a bit “hair on fire” about this issue, I am certainly not predicting the imminent collapse of the addiction treatment industry. The industry has survived worse shocks than this, and it’ll survive this too. I’m not trying to scare you into hiring Faebl, although if you need help navigating this, we’re here and we know what we’re doing.

What I’m trying to do is give you a clear-eyed look at structural forces that most facility operators haven’t fully connected yet. I’ve spent the last week talking to clients and colleagues, and the most common response I’m getting is some version of “I knew the subsidy thing was a problem, but I didn’t realize how directly it affects us.”

That disconnect is what I’m trying to fix. Because the connection is direct. It’s mechanical. It’s predictable. And it’s coming fast.

I built my business around solving exactly these kinds of problems. I spent years working in and around this industry before I started Faebl. I’ve lived through policy changes and market shifts and payer crises. I care deeply about the people behind these policies, both the clients who need treatment and the facility operators who are trying to provide it in an increasingly hostile reimbursement environment.

And I can see what’s coming here. The ground is shifting, and it’s going to accelerate. The facilities that understand the shift and prepare for it now will be the ones still serving clients when the dust settles. The facilities that assume it’ll work itself out, or that Congress will fix it before it becomes a real problem, or that their market is somehow insulated from these dynamics are going to get caught flat-footed.

If the subsidies expire, millions of people will lose access to affordable coverage. Facilities will face real financial pressure, some of it existential. People who need treatment won’t be able to access it, and some of them will not get another chance. That’s not a political talking point. That’s the straightforward result of the policy decision that’s in play.

The time to do something about it is now. Not in March when you’re looking at your Q1 numbers and trying to figure out why your admissions are down 20%. Now.